Recently, I did a presentation at one of my company’s events where I talked about concurrency in Go. I’ve decided to turn that presentation into a blog post and share the content here too.

Table of Content

In this presentation, we’re going to talk about concurrency in the context of Go. First, we’ll cover what concurrency actually is and why it matters. Then we’ll look at Go’s approach and the tools it gives us. After that, we’ll walk through three important considerations when using these tools, with examples and how to fix common issues. I’ll also share how we handle these challenges in our company. Finally, even though I talked about some well-known concurrency patterns in the presentation, I won’t repeat them here since I already wrote a separate blog post about Go concurrency patterns.

What is Concurrency?

When it comes to concurrency, there are lots of quotes and definitions depending on the context. But I want to explain it with a simple example so we’re all on the same page.

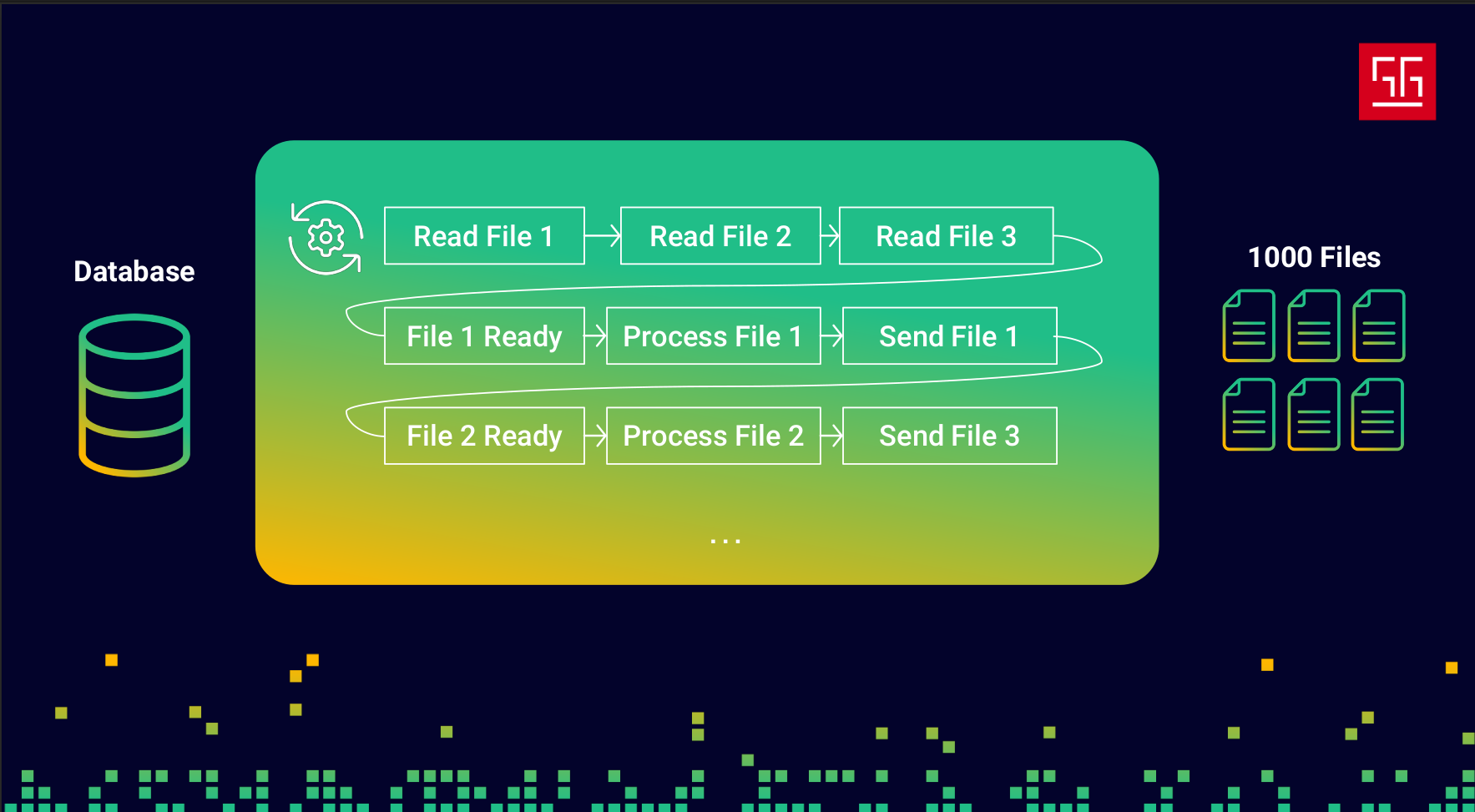

Let’s say they ask me, as a software engineer, to develop an application that reads 1000 files, processes them, and saves the results into a database. Like any developer, I’d probably start by writing something like this:

- Read File

- Process File

- Send it to DB over network

Alright, everything works and the code is fine. But then they ask me to make it faster — they want these files to be processed in less time. And like any developer, the first thing that comes to mind is: “More speed? Easy. Give me more resources!” So I ask for four CPU cores and more memory so I can run four instances of my application. It would look something like this:

Okay, now I can process the files about three to four times faster than the previous approach. But then they come back and say, “We don’t have the budget to spend on more resources… and we still want better performance!”

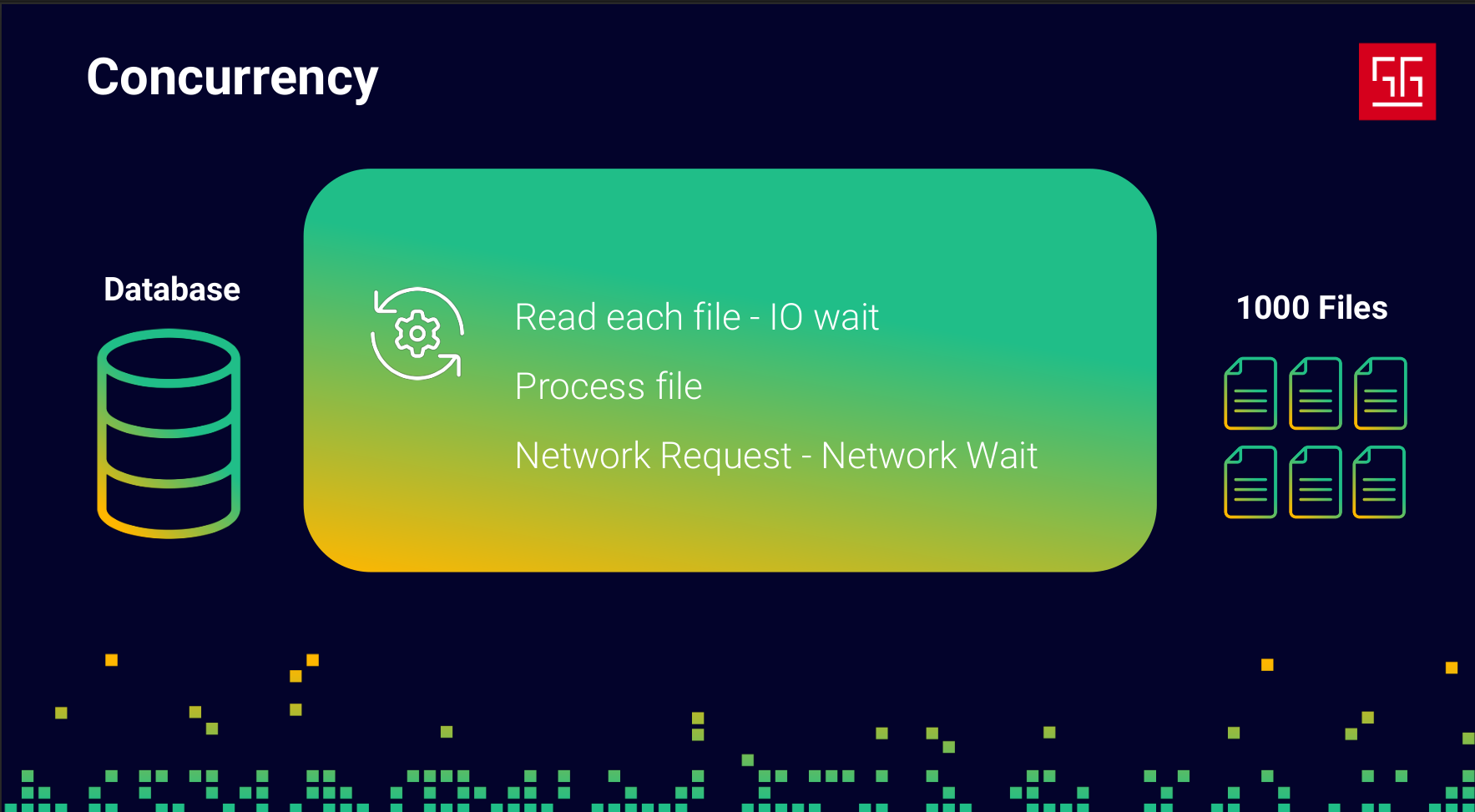

Now things get a bit complicated. So I decide to focus on the code itself and check my monitoring tools to see what I can improve.

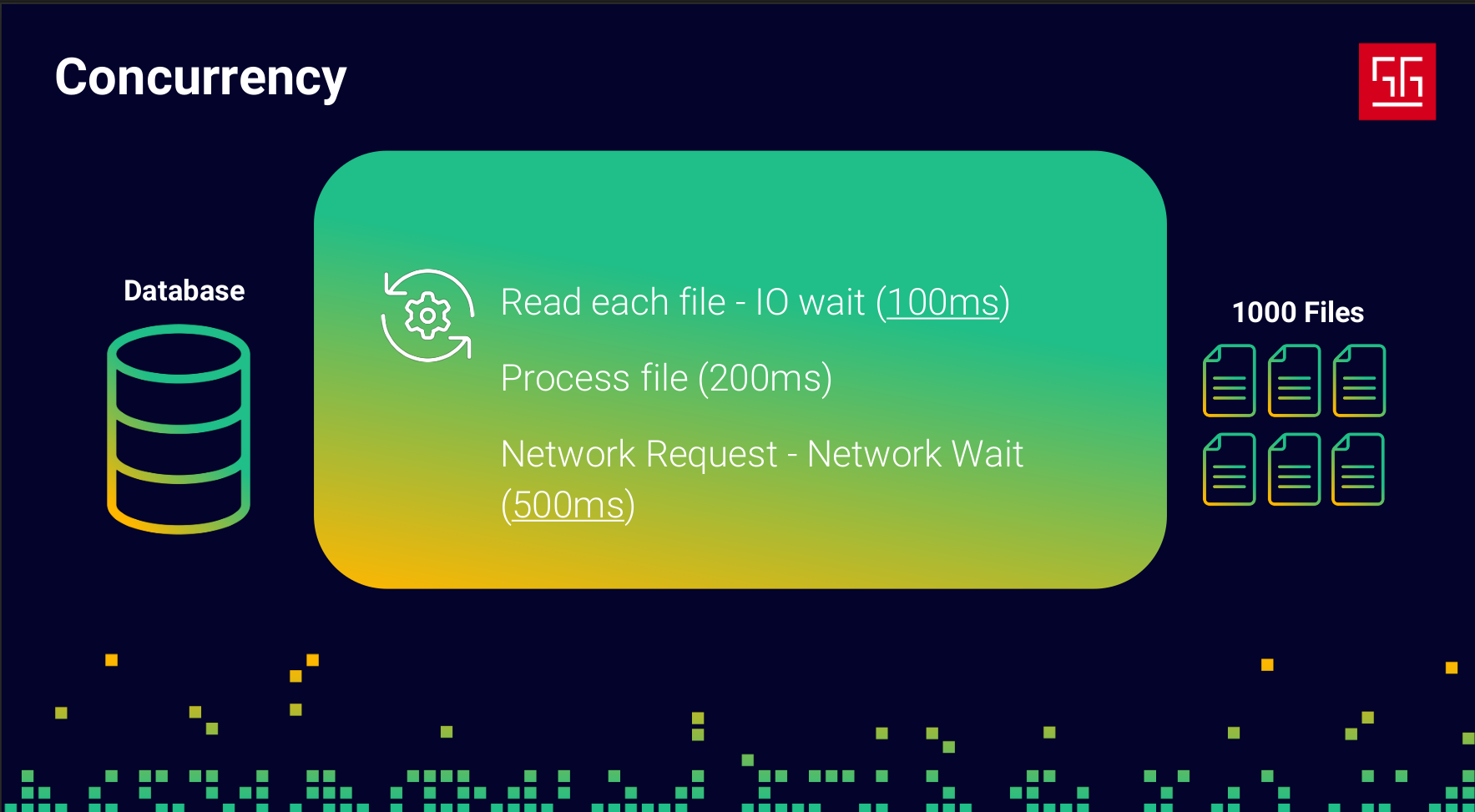

I found out that reading each file takes around 100ms, processing takes about 200ms, and the database request takes roughly 500ms. I already wrote the processing part in the most efficient way possible — it’s O(n) and can’t really get any faster. But what about the reading and the DB request? In both of those steps, my program is basically idle, just waiting for I/O to respond. So I started thinking… what if I use that idle time?

So I changed my code so it doesn’t sit there waiting for external operations to finish. Instead, it moves forward and works on other tasks, and when the result is ready, it comes back and continues the job.

So my code ends up looking something like this: it reads file 1, then file 2, and so on. Once file 1 is ready, it starts processing it, and meanwhile, file 2 becomes ready and gets processed, and this continues. As you can see, the processing part never stays idle — I’m effectively using that 600ms of waiting time.

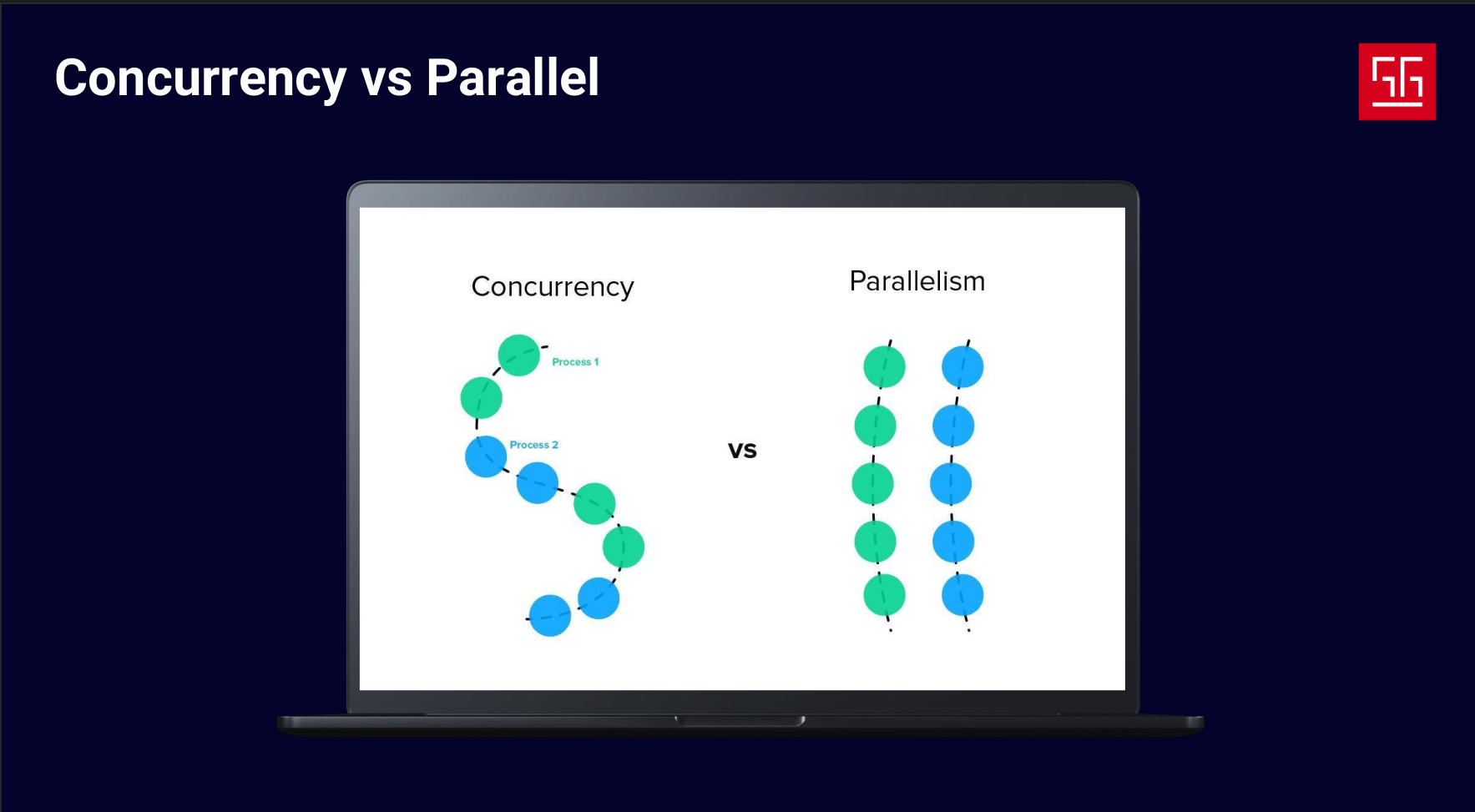

As you could see in the example, I had two approaches to increase speed and efficiency. The first was a parallel approach — running multiple instances of the application — and the second was a concurrent approach. In concurrent approaches, we move along multiple tasks, but we’re not doing them at the exact same time. We do a few steps of one task until it’s blocked, then switch to another task. In parallelism, on the other hand, two or more tasks are actually executed at the same time. The key point is that parallelism requires multiple CPU cores — you can’t truly run two parallel tasks on a single core.

The point is, concurrency isn’t just about increasing efficiency. In many cases, we need to write concurrent code to provide the best experience for our users.

Writing concurrent code, managing flows, and designing logic can be really hard. Sometimes junior developers think the struggles they face with concurrency are just due to lack of experience. But that’s not true — it’s a global challenge. Anyone who has worked with concurrency or thread libraries in any language will realize how complicated it can be, from managing and sharing data between threads to dealing with locks, data races, context switches, and more.

Even at Google, this was a challenge. As Rob Pike mentioned in one of his talks, threads were banned in some projects to avoid dealing with their complexity. In fact, one of the main reasons the Go project started was to address these concurrency issues.

There are multiple ways and approaches to write concurrent code.

The first and most classic approach is to use OS threads and mutex locks directly. The problem is that threads are hard to manage and are also expensive resources.

Another approach is the Async & Await pattern, which JavaScript is famous for, though there are libraries for this in other languages as well. In this approach, you create callbacks for async tasks and run them when they’re ready, while other ready tasks can continue executing. This approach is nice because you don’t have to manage threads directly, but the downside is that it forces a specific coding style.

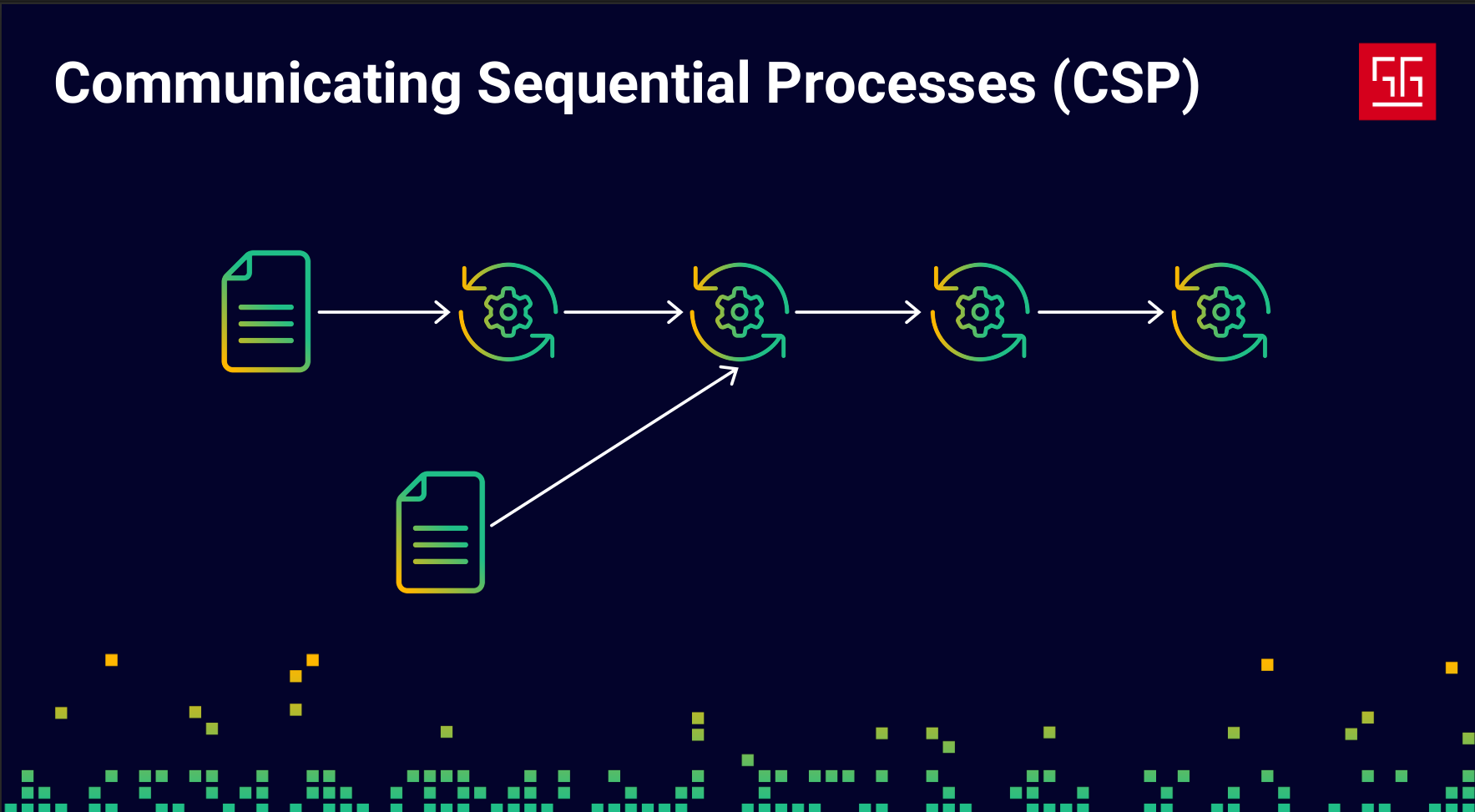

Another approach is Communication Sequential Processes (CSP), which comes from a paper with the same name. In short, it allows you to define your logic as sequential flows and pass data between them, enabling communication between different parts of your program. Go also uses this approach.

Golang Approach

As I mentioned before, Google faced this problem with threads and concurrent logic, so they decided to address it in Go. The main idea behind Go — and the key difference between Go and languages like C++ or Java — can be summed up by this quote: “The world is parallel and concurrent, not OOP.”

To understand how Go implements concurrency, let’s see how Rob Pike defines it:

This definition has two key parts: the first is “composition,” and the second is “independently executing things.” So Go needs to provide tools and syntax to handle each of these parts.

lets focus on "independently executing things".

Goroutines

The first tool Go provides is Goroutines, which let us run a function independently from the main code flow. Let’s take a look at how goroutines work and what happens when we start one.

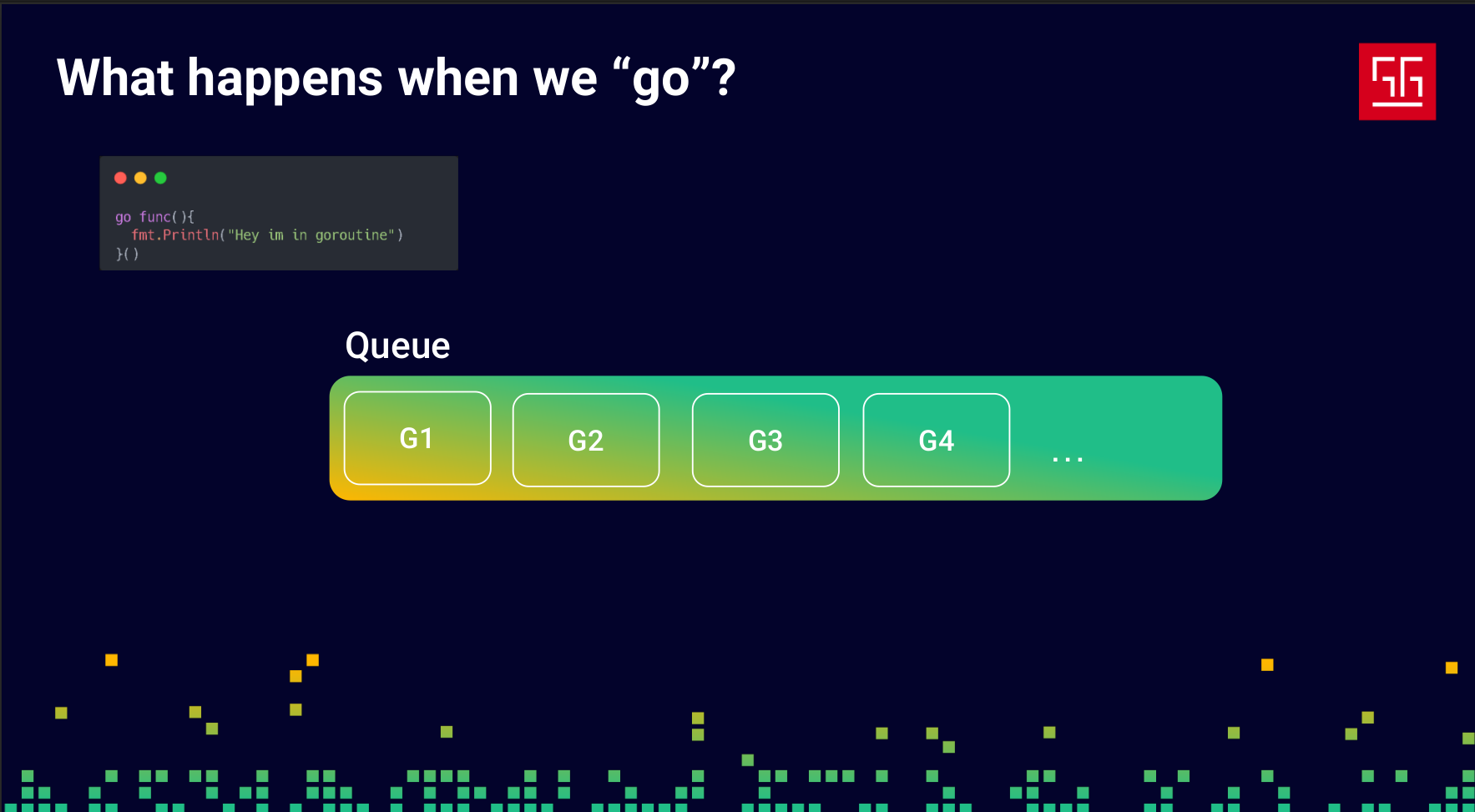

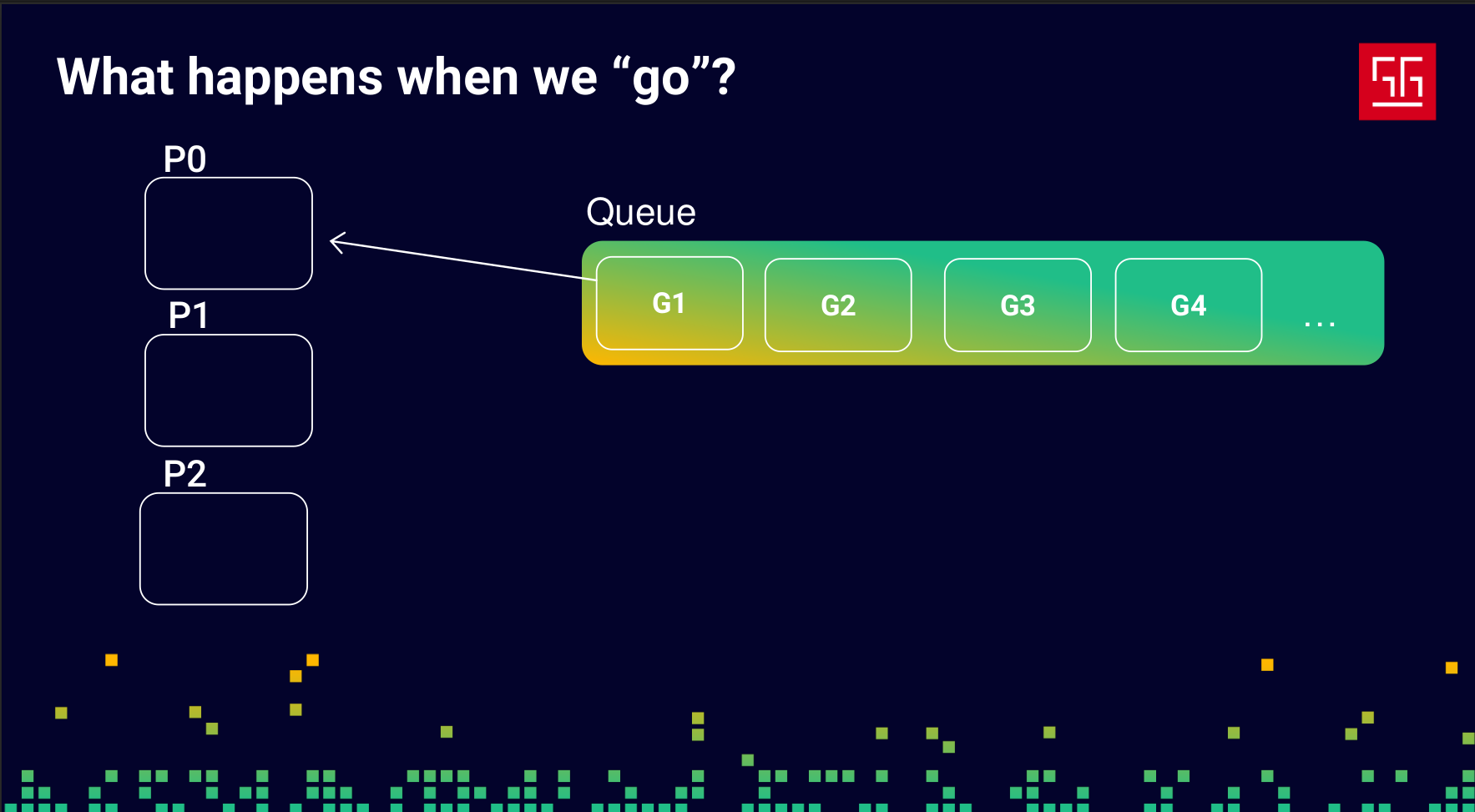

A goroutine doesn’t start immediately — first, it goes into a queue.

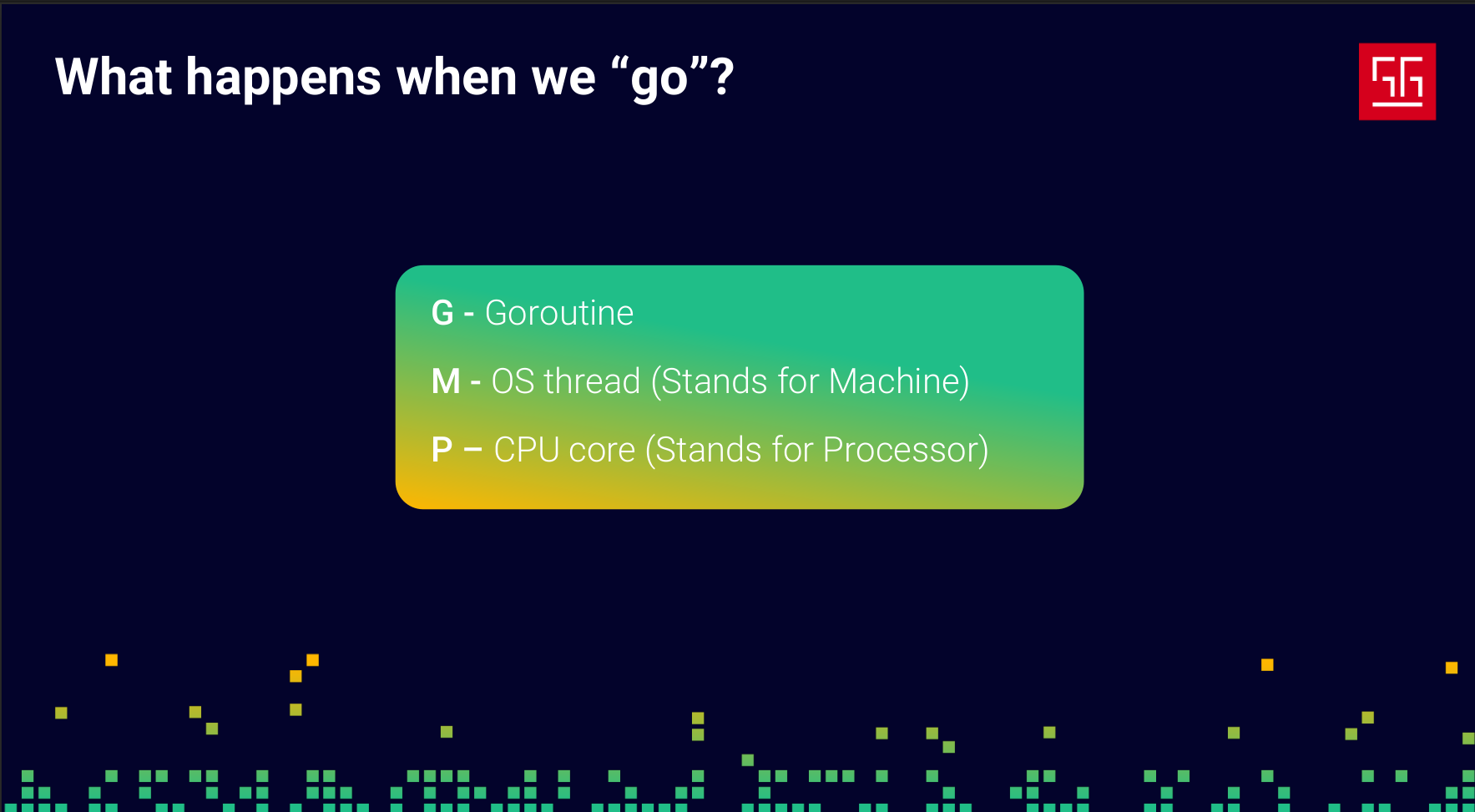

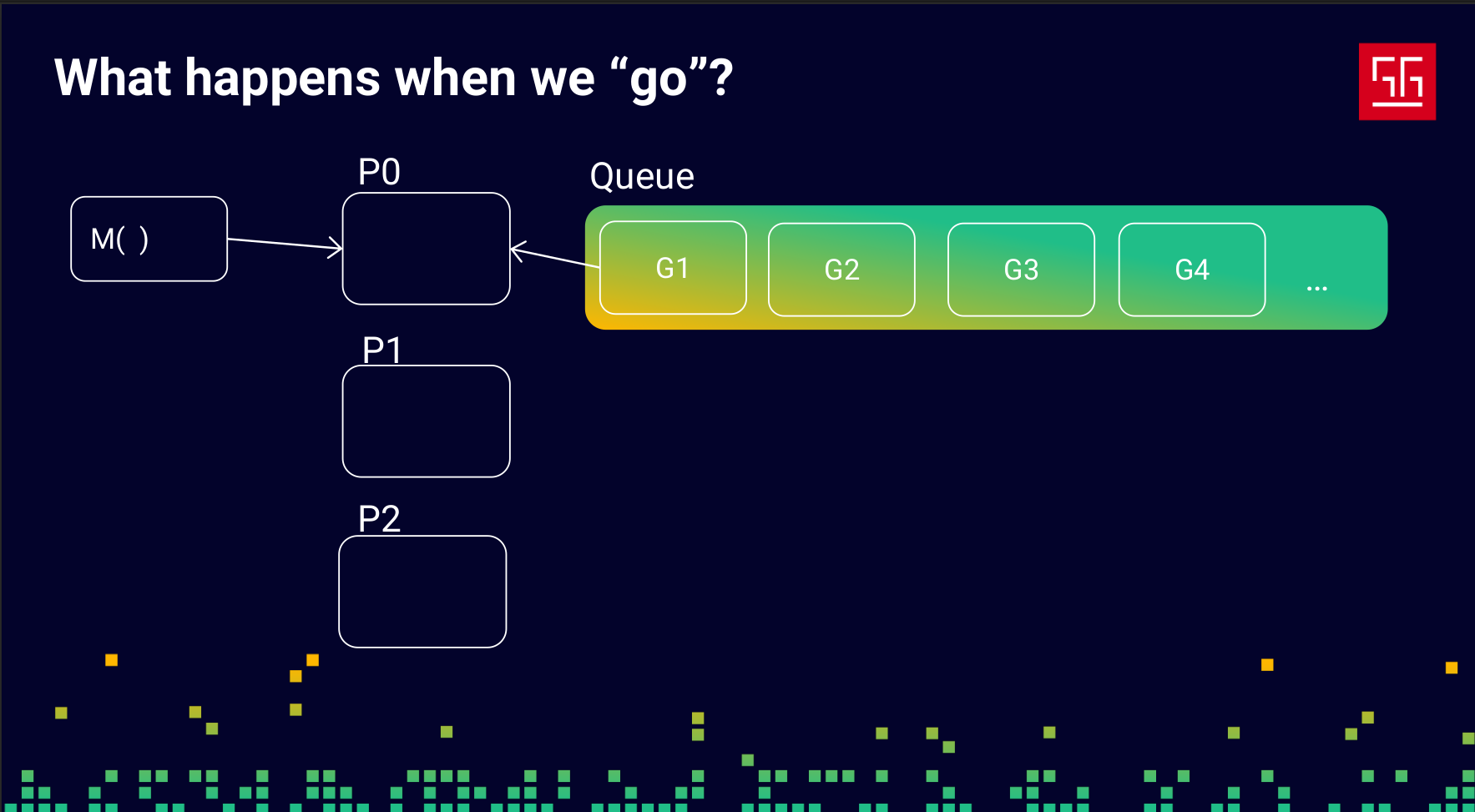

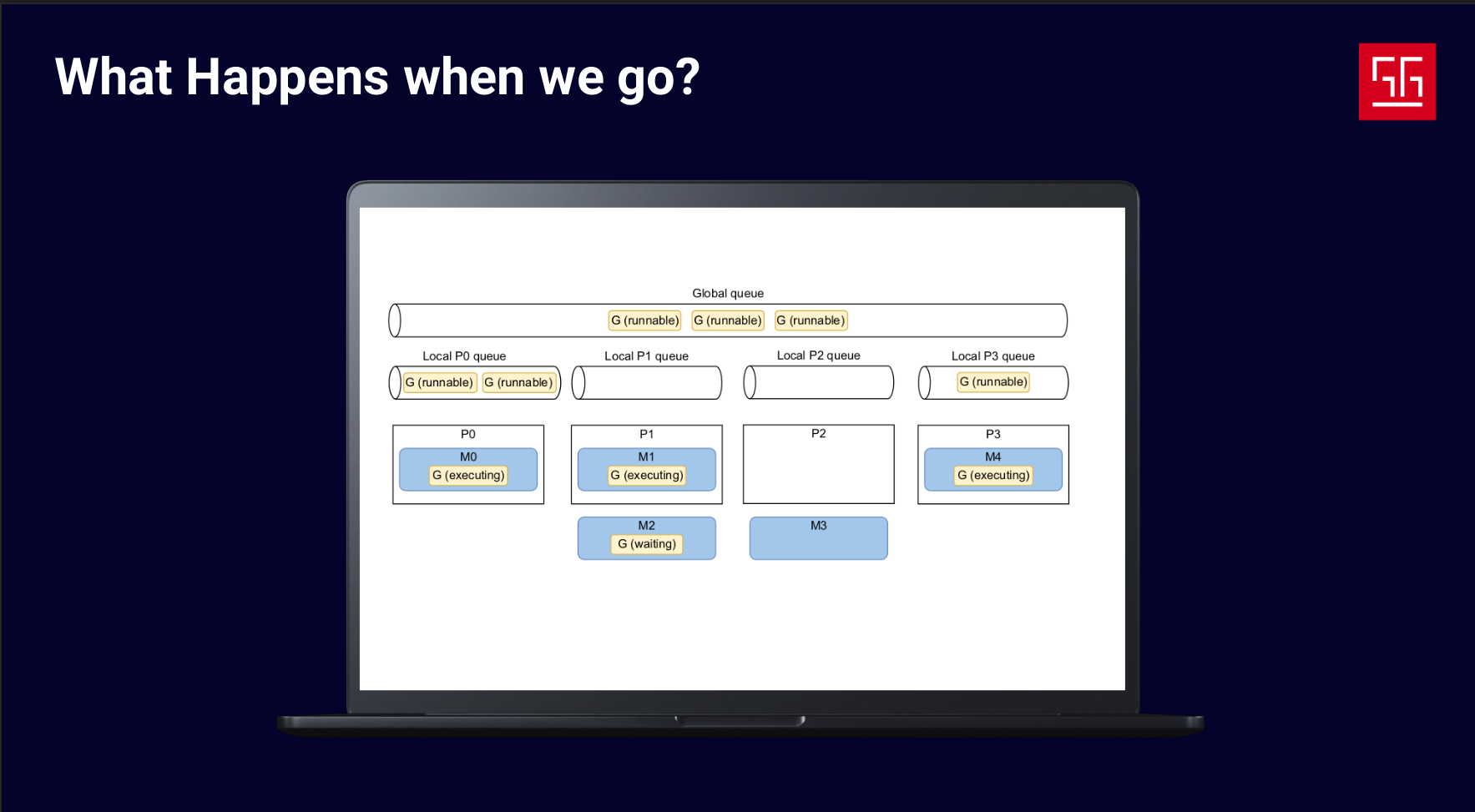

Before we continue, let’s define some names: we’ll call goroutines G, OS threads M, and CPU cores P. The important thing is that P isn’t exactly a CPU core — it’s a Go process, an abstraction over a CPU core. You can configure and change it based on your needs, but by default, the number of Ps in Go matches the number of CPU cores.

So, as we said, the Gs (goroutines) go into a queue, and the Ps are processes created to match the number of your CPU cores, as shown in the slide.

The responsibility of these Ps is to create Ms (OS threads) and take Gs (goroutines) from the queue to run them on an M. When an M is waiting for the network, a lock, or any other blocking operation, the P will put that M and its G into the queue and pick another G to run. This way, your process never stays idle.

Here’s a more detailed image of the GMP model. I took this one from the book 100 Go Mistakes and How to Avoid Them.

Channels

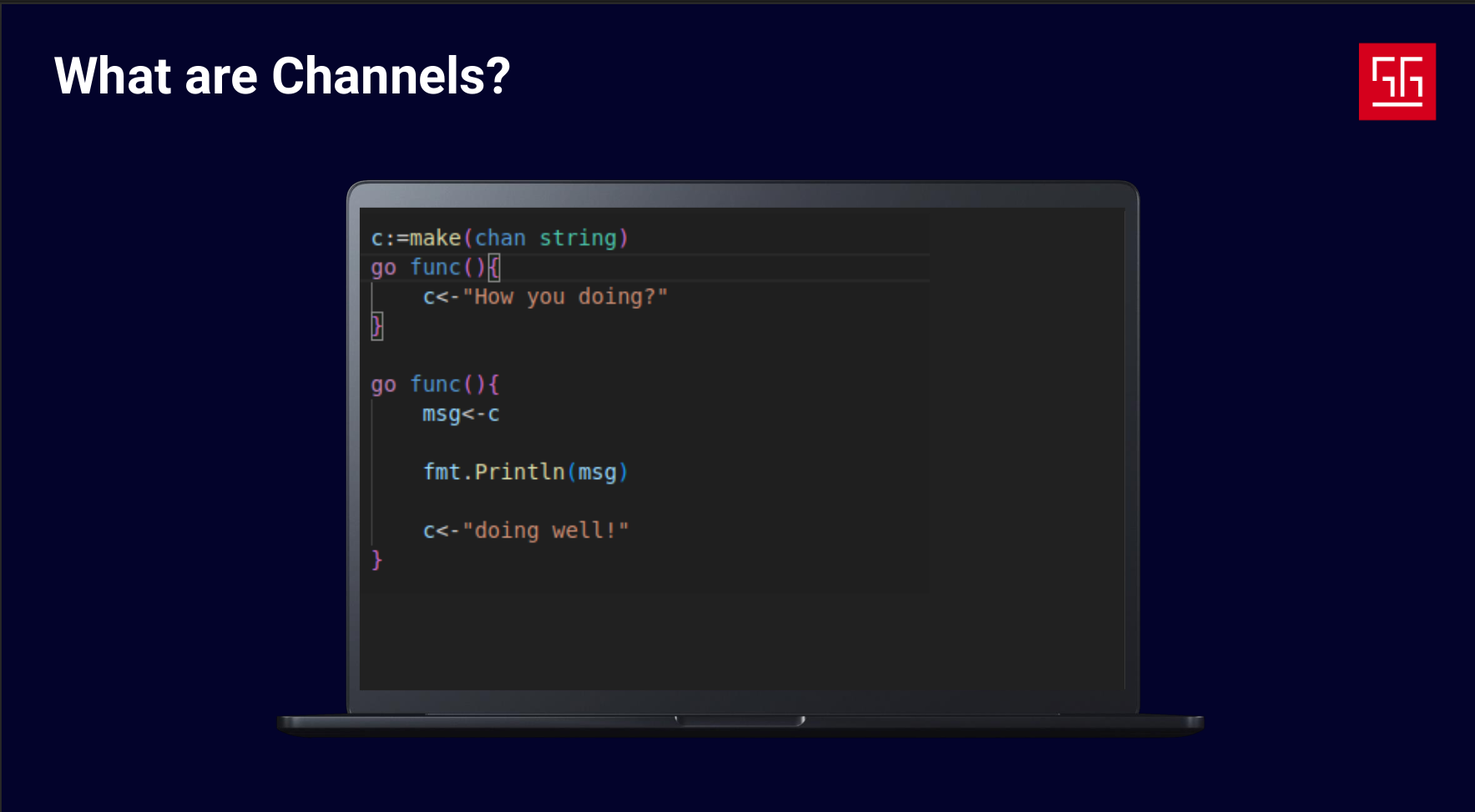

Goroutines handle the “independently executing things” part, but what about the “composition” part? To achieve this, Go provides channels. Channels are tools for sending data between goroutines and enabling communication.

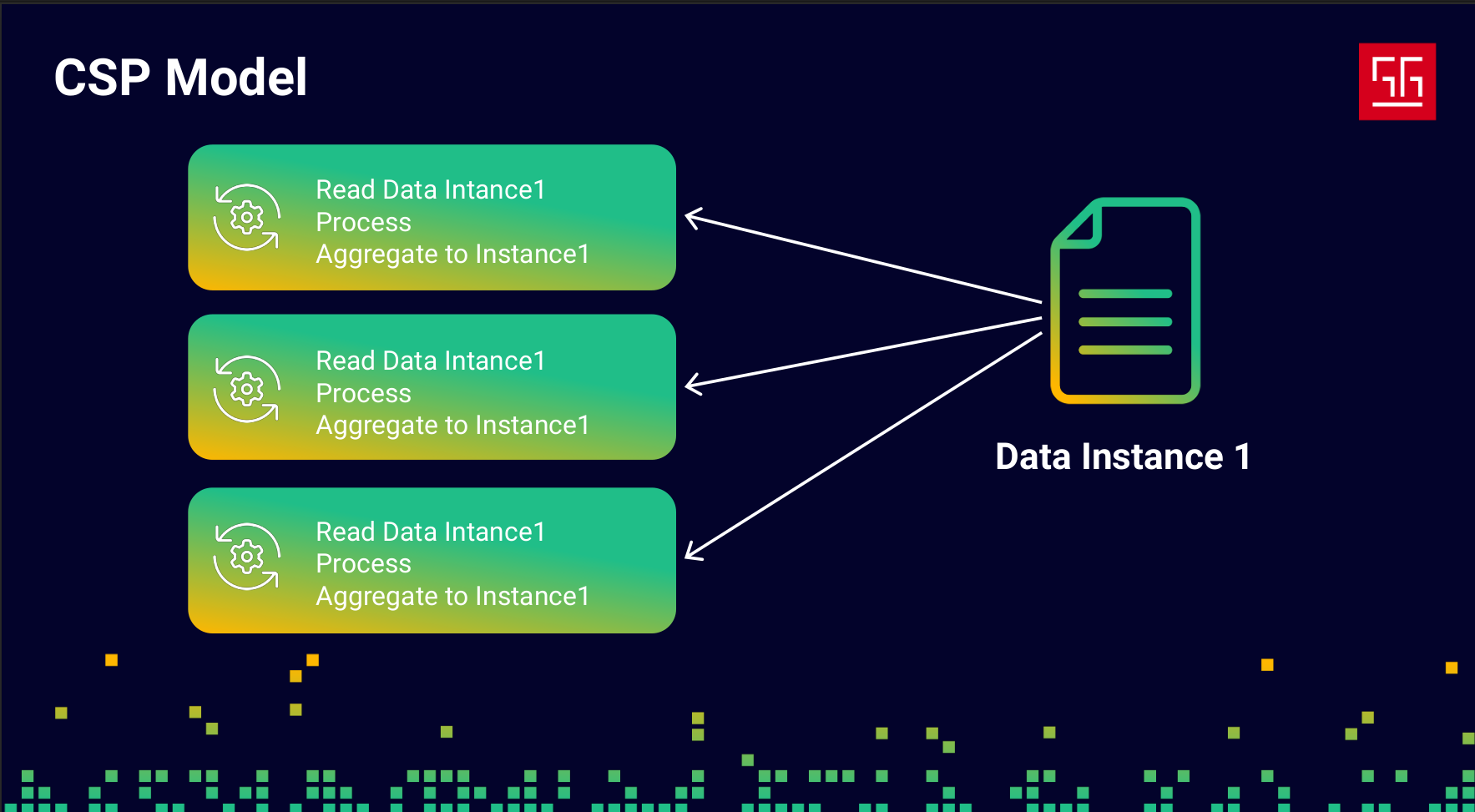

You might ask, “What’s the point of channels if goroutines already share memory? Why not just use memory to share data?” That’s exactly where CSP comes in. Let’s explain this with an example.

Let’s say I have three goroutines, and they’re all trying to process the same data instance. First, they read the data, then process it, and finally write the aggregated result back into the instance. In the classic approach, I would use locks to prevent data races. But this time, let’s see how we can handle it using channels and CSP.

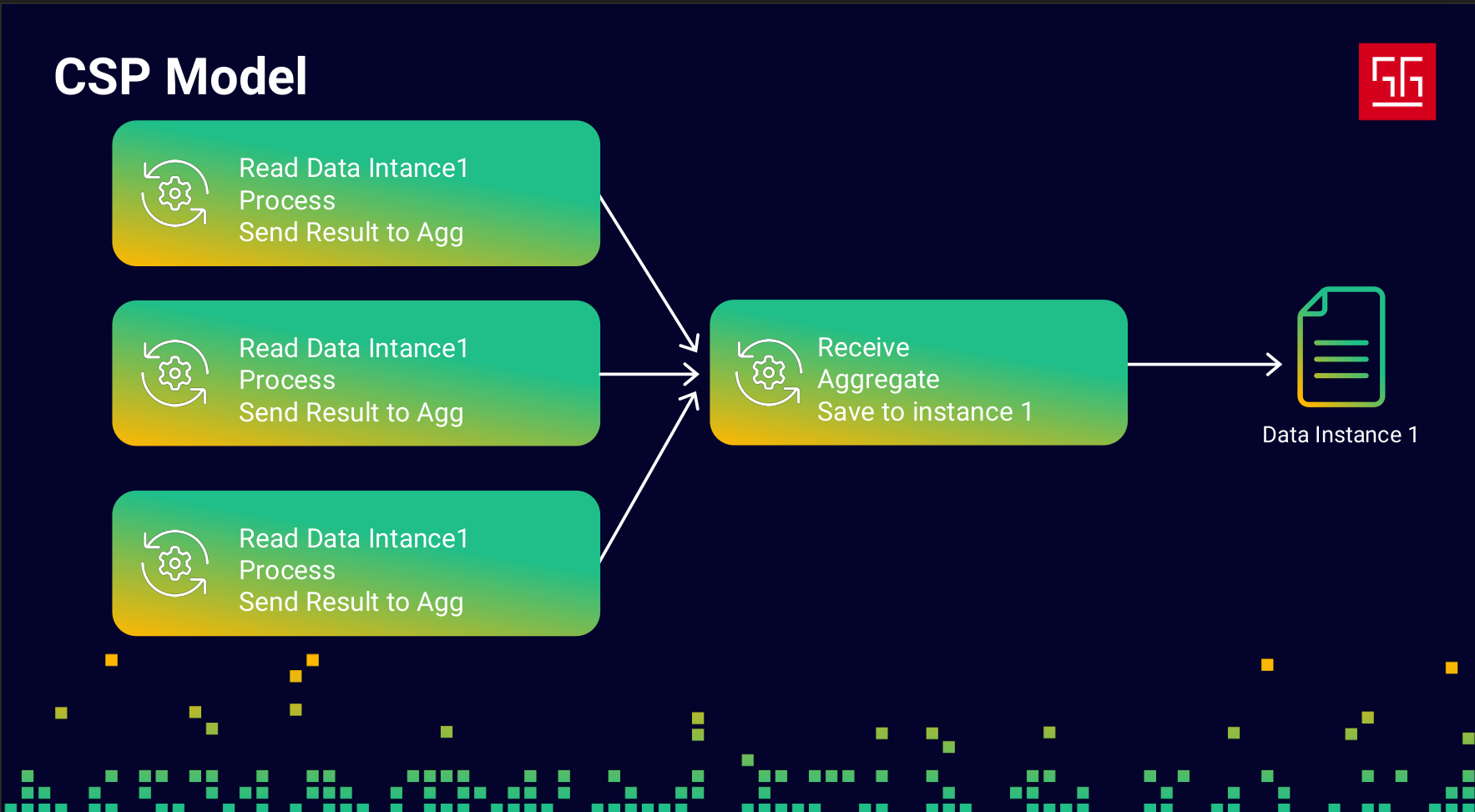

I changed my code into a sequential flow with two steps: the first step reads and processes the data, and the second step aggregates the results into the data instance. I used channels to send data from the first step to the second. In this approach, I didn’t use any locks only Go channels. The key point is that this prevents any race conditions.

Considerations

Go has simple interfaces and is easy to learn, but because so much complexity is handled behind the scenes, mastering it can be challenging. Using interfaces to manage this complexity won’t always give you a perfect solution — you need to understand what’s happening under the hood.

Unbounded Concurrency

Let’s say I have this piece of code:

wg := sync.WaitGroup{}

for range 1_000_000 {

wg.Add(1)

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

time.Sleep(time.Minute * 10)

}()

}

wg.Wait()I’m using goroutines to process 1 million records, and each one takes 10 minutes. I run it, and it works fine. But when I monitor memory usage, I see around 3GB taken by my app even though I don’t have any large arrays or big data, and I barely define any variables. What’s happening?

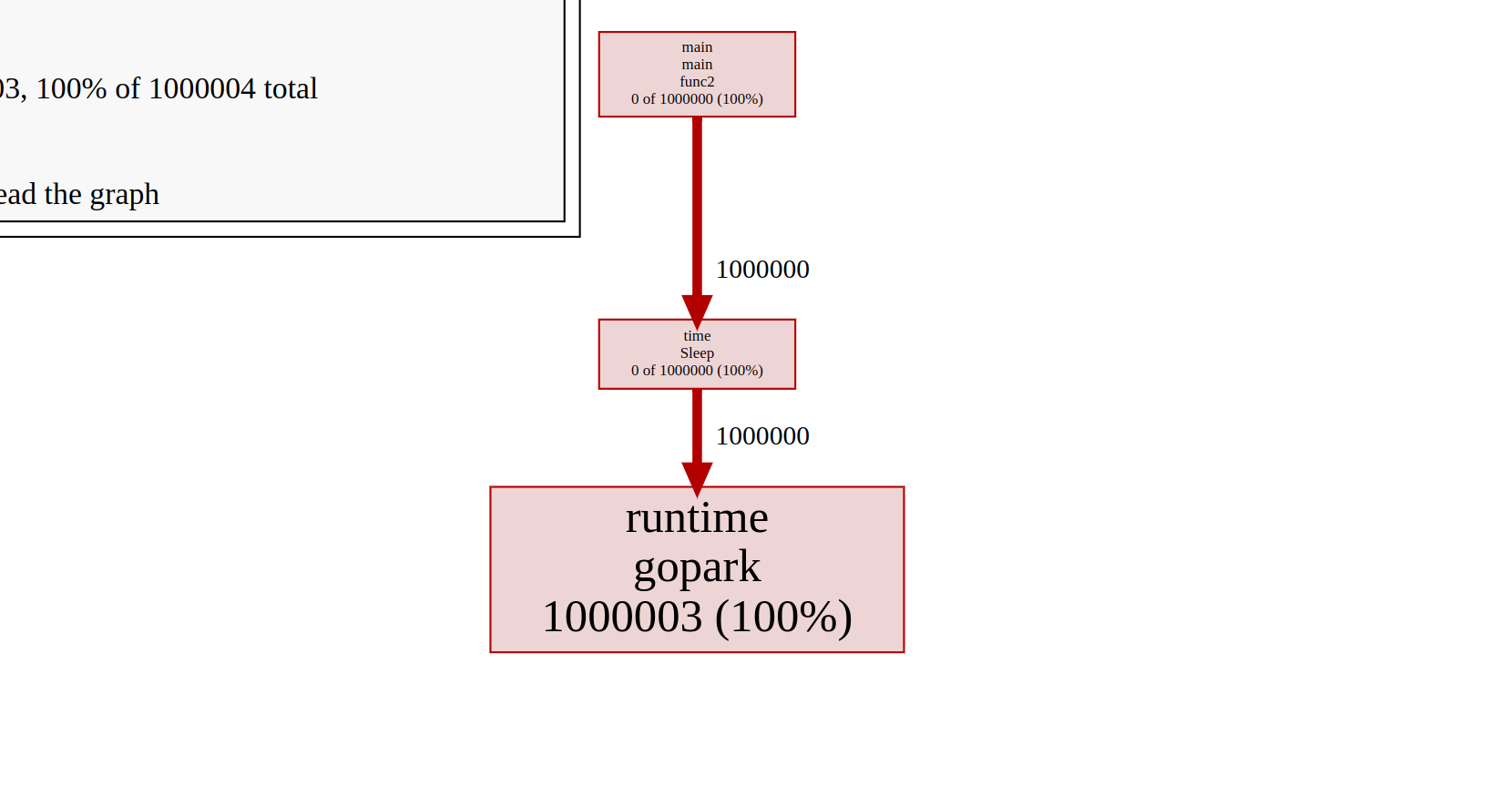

To investigate, I used pprof to check the state of my goroutines.

Here, I have 1 million goroutines, all in the Gopark state, which means they each have a thread and are waiting for something. The issue is that each goroutine comes with a stack size of about 2KB–4KB, and the stack will grow or shrink as needed.

I only have 8 CPU cores, so running this many goroutines will just consume a huge amount of memory. You always need to bound the number of goroutines you start. To fix this, I used buffered channels to implement a rate limiter.

wg := sync.WaitGroup{}

limiter := make(chan struct{}, 10)

for range 1_000_000 {

wg.Add(1)

limiter <- struct{}{}

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

time.Sleep(time.Minute * 10)

<-limiter

}()

}

wg.Wait()Another common approach to this problem is using the Worker Pattern, which helps limit the number of running goroutines at any given time.

Data Race

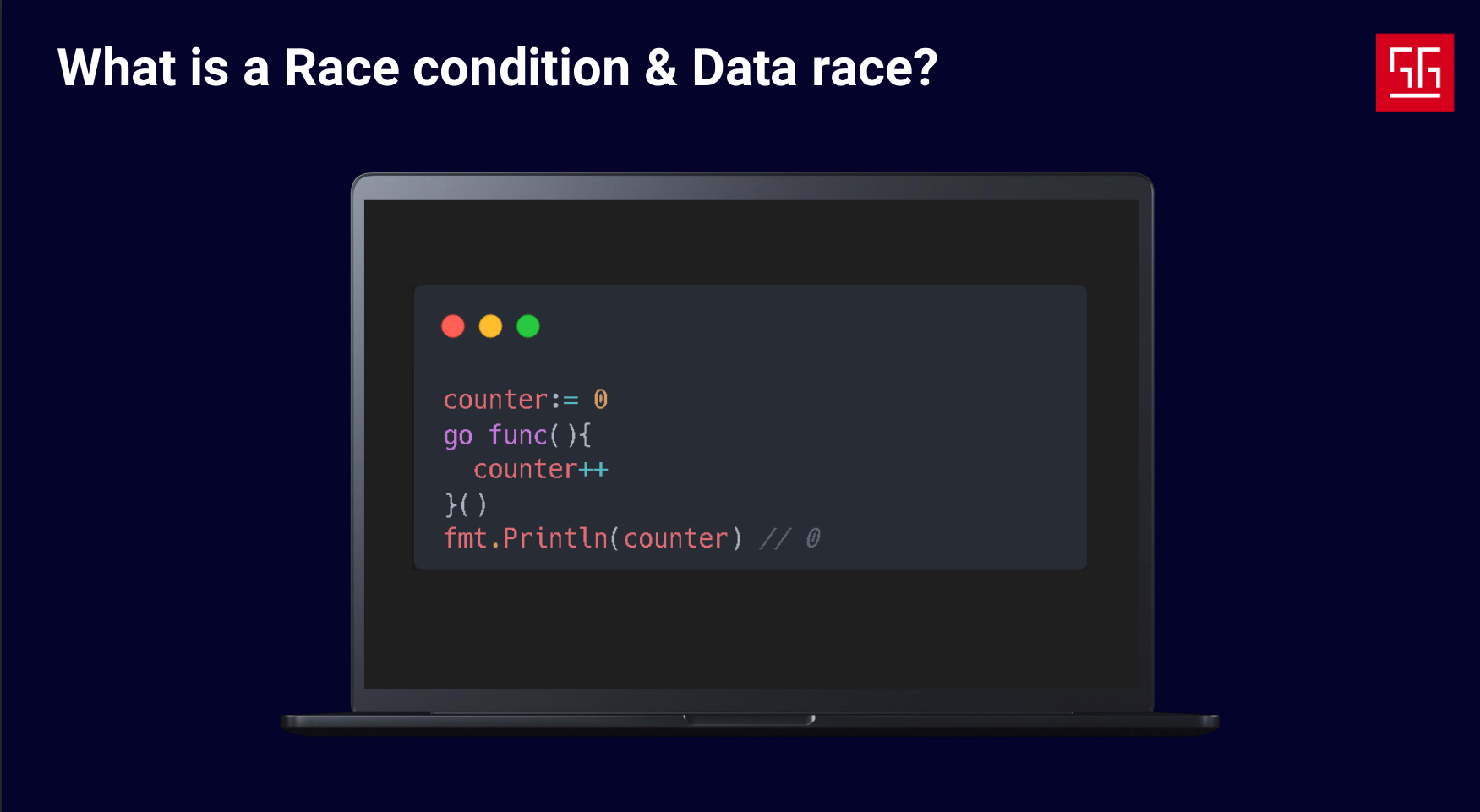

Data races are a common concurrency issue, and you’ll encounter them no matter which approach you use. But first, let’s see the difference between a data race and a race condition.

- Race condition: This happens when your code relies on the timing or order of instructions, and because of concurrent logic, you can’t guarantee that order.

- Data race: This occurs when two processes access the same memory location and at least one of them is writing. The problem is that you can’t rely on the data, and the output becomes nondeterministic, depending on what happens at the CPU level.

Let’s look at an example:

func main() {

counter := 0

for range 1000 {

go func() {

c := counter

c += 1

counter = c

}()

}

time.Sleep(2 * time.Second)

fmt.Printf("%d \n", counter)

}

This code obviously has a data race and will not reliably output 1000. So how can we fix it?

First approach: using locks

func main() {

mu := sync.Mutex{}

counter := 0

for range 1000 {

go func() {

mu.Lock()

c := counter

c += 1

counter = c

mu.Unlock()

}()

}

time.Sleep(1 * time.Second)

fmt.Printf("%d \n", counter)

}

I added a mutex, and now the data race is fixed.

Second approach: using channels and CSP

I’ll change the logic into a two-step sequential flow. The first step sends values, and the second step aggregates them:

func main() {

ch := make(chan int)

go func() {

total := 0

for v := range ch {

total += v

}

fmt.Println("Counter:", total)

}()

for range 1000 {

ch <- 1

}

close(ch)

time.Sleep(time.Second)

}

To be honest, both approaches are valid, but when should you use each? In the CSP approach, channels are used to communicate between processes. So, whenever your problem is about communication between concurrent tasks, channels are the more natural choice. Locks are more suited when you just need to protect shared memory without restructuring your logic.

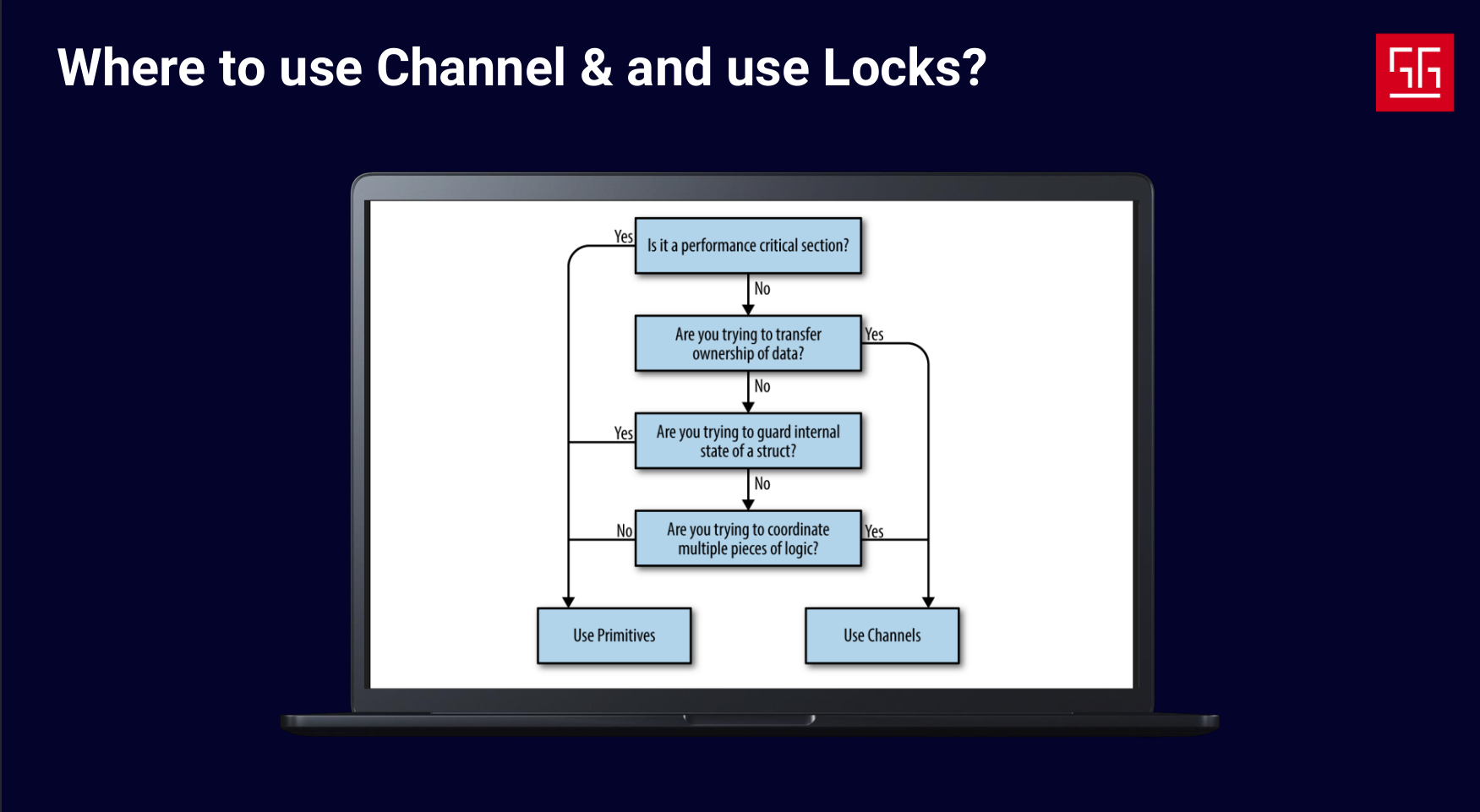

I took this image from the book Concurrency in Go, which shows a decision tree for whether to use channels or locks.

The last three steps in this tree are pretty obvious, but the first one says: when you’re developing a performance-critical section, use locks.

Why is that? Does it mean channels aren’t performant? Absolutely not. Channels are essentially just a queue plus a mutex lock. The main point of using channels is to write cleaner code and prevent race conditions in the first place. But if you’re extremely concerned about performance, locks can be the better choice.

Scheduler Behaviour

Sometimes the scheduler’s behavior can cause unexpected issues. Let’s see an example:

func main() {

runtime.GOMAXPROCS(1)

go func() {

for {

for range int(1e15) {

for range int(1000) {

_ = 1 + 1

}

}

}

}()

time.Sleep(time.Second * 1)

ticker := time.NewTicker(100 * time.Millisecond)

start := time.Now()

for i := 0; i < 20; i++ {

<-ticker.C

fmt.Printf("\n[%v] tick %d", time.Since(start).Round(time.Millisecond), i)

}

}

In this code, I have a goroutine performing heavy CPU tasks and a main goroutine that prints the time every 100ms. If you run it, you’ll notice that the ticker prints with delays.

But why does this happen?

As you can see, I’ve set GOMAXPROCS to 1, so there’s only one P in this app. The first goroutine is performing heavy CPU work and never gets blocked by network, locks, or I/O. So based on what we know, the P will start running it and never stop.

But here’s another question: if the P is busy running the first goroutine and there are no other Ps to run the ticker’s routine, why does the ticker still print?

If you run this code with an older Go version, like 1.13 or lower, the ticker won’t print. But why does that happen?

In older Go versions, the scheduler was cooperative. This meant goroutines had to cooperate to give up their Ps, and they tended to keep running once they were assigned to a P.

In newer Go versions, the scheduler was changed to preemptive. This means that at certain points, each goroutine can yield its P to other goroutines, preventing starvation and ensuring that all goroutines get a chance to use resources.

Okay, but why does the delay still happen?

Go automatically injects preemption points in your code at certain places, like loops or function calls, to yield goroutines. The problem is that Go doesn’t know the logic of your program, so it might not find the best spots to yield.

To handle this, the runtime package provides a method called runtime.Gosched(). By calling this inside a goroutine, you can explicitly yield it. To prevent the delay, I changed the code like this:

func main() {

runtime.GOMAXPROCS(1)

go func() {

for {

for range int(1e15) {

for range int(1000) {

_ = 1 + 1

}

runtime.Gosched()

}

}

}()

time.Sleep(time.Second * 1)

ticker := time.NewTicker(100 * time.Millisecond)

start := time.Now()

for i := 0; i < 20; i++ {

<-ticker.C

fmt.Printf("\n[%v] tick %d", time.Since(start).Round(time.Millisecond), i)

}

}

At safe points, a goroutine will yield and let other goroutines use the resources. The key is not to use Gosched() everywhere — only at certain safe points. If you call it in the wrong place, it won’t help and will just make your code slower by adding scheduling overhead.

What we do?

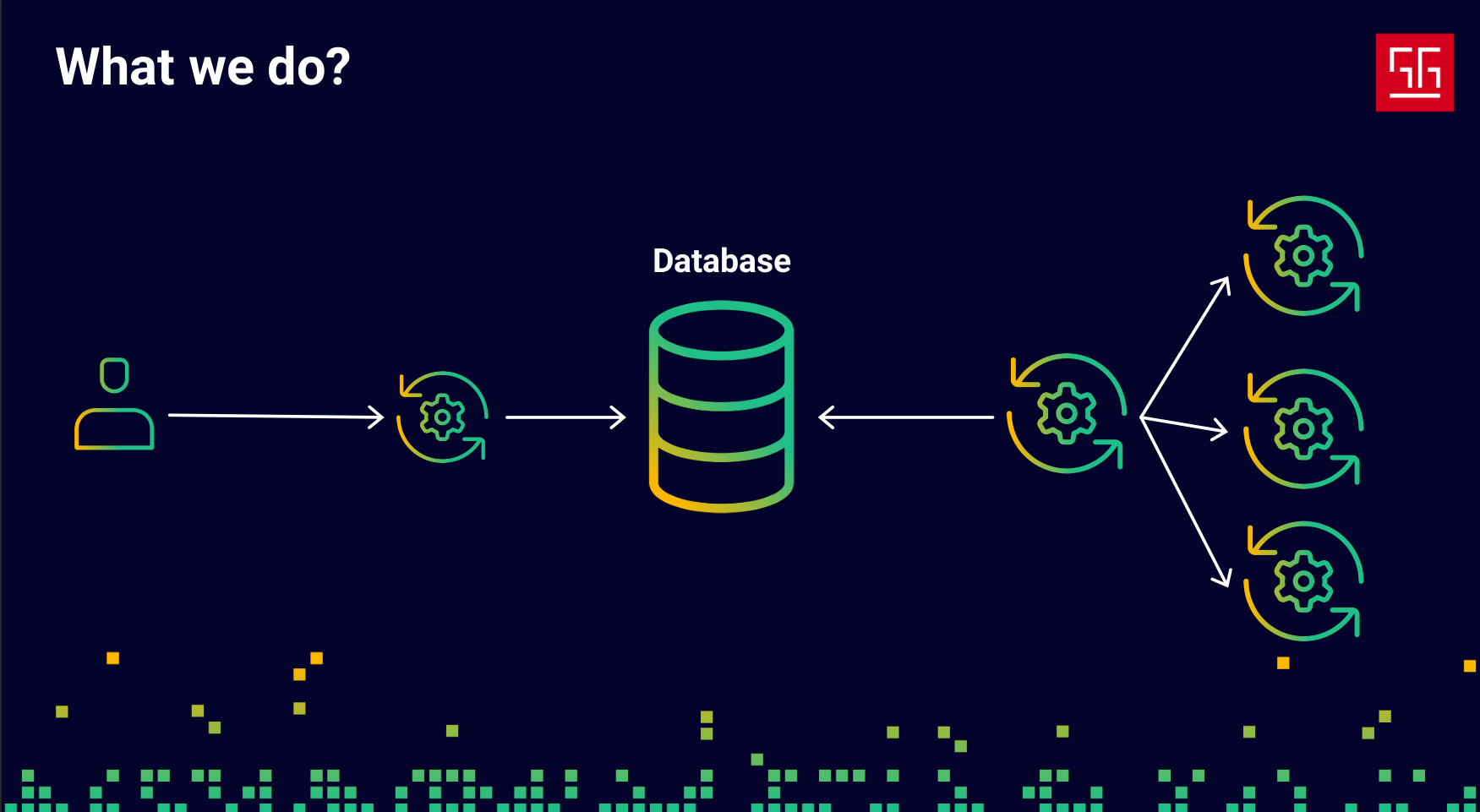

Okay, we’ve talked about how Go’s concurrency works and some key considerations, but there are still many other things to watch out for when using goroutines and channels. In our company, we have over 80 developers working full-time on a data-intensive ERP application, which means a huge amount of code is generated every day. We can’t catch every issue in code reviews, and we definitely can’t risk data corruption, since the data we handle is B2B financial management data — extremely critical and important.

We don’t use goroutines directly. Instead, we implemented a job infrastructure that creates a main goroutine responsible for running other goroutines and managing them based on their state in the database. All of our heavy async tasks run through this system.

Conclusion

As Rob Pike says, “Simplicity is complicated.” It’s really hard to cover complex logic using simple interfaces and still make it useful. The most important thing about Go is that it tries to balance both simplicity and power, which is what makes it so wonderful. But as users, it’s crucial for us to understand how these tools work to get the most out of them.

Thanks for reading! I’d really love to hear your thoughts and ideas — feel free to reach out!